South Africa's cool-climate whites and scorching reds: why the country has it all

The 93-point Rijk’s Chenin Blanc Tulbagh Reserve 2014 is a full-bodied and layered white that boasts fruity aromas and lively acidity.

South Africa is on its game for white wines

Wine lovers, take note: South Africa is on its game for white wines! The country’s whites are now deserving of every wine consumer’s attention, not least for the excellent value they have to offer.

As James and I tasted through almost 500 wines from the country in May this year, we could not help but be amazed as one outstanding flight followed the next of chenin blanc, chardonnay and even sauvignon blanc.

Until only too recently, much of the white grapes grown in the Cape found their way into bulk wine, brandy production or, at most, catered solely to the whims of the market. While the majority of South African wine is still not exported in bottle, the premium sector is following a formula to a tee, harvesting with high acidity levels and fermenting their whites bone-dry, very rarely overdoing the oak.

“We’ve become much more precise in our white wine production, but it all starts in the vineyard,” says Anton du Toit of Rhebokskloof estate. “Here at our winery in Paarl, we have decided sauvignon blanc just doesn’t work, so we’ve pulled it out. In the past, we would plant according to what the market wanted; often in the wrong place. Now, we try to grow chenin, for example, only on sites where the grape can keep its natural minerality.”

In fact, the whites are so dependable that if in doubt, a safer bet would be choosing them over the reds. South African cabernets and Bordeaux blends in particular, usually from hotter areas, can have the tendency to slip into slightly overripe or overworked territory.

It’s almost counterintuitive that the only serious wine-producing country in Africa — the continent better known for its arid deserts and barren savannas — should be outdoing itself with its white wines.

A new wave of cool-climate reds are leading the way

What’s more, some of the exciting red wines are now being made in indisputably cool-climate areas, most of them are barely a few decades old.

“I think it’s a perception thing,” explains Jason Snell of The Drift, a wine estate making fabulous pinot noir and syrah in the up-and-coming Overberg district. The mountainous region begins roughly 70km southeast of Cape Town on the Cape South Coast. “People think all of South Africa is hot, but this is far from the case. We’re at 450m above sea level, embraced by the side of a mountain, and the cool breeze from the Atlantic comes right over the top every morning at about 10 o’clock. Here, we usually place ourselves somewhere between Burgundy and Bordeaux in terms of climate.”

Why South Africa is not as hot as you think for cool-climate varieties

At 33.9° S latitude, Cape Town shares the same distance from the equator with parts of Morocco and Algeria. Yet, studies consistently put Overberg into the region II band within the Winkler Index, a widely used system for classifying wine-growing climates according to the total heat over the growing season (growing degree days). In short, this means comparisons to cooler temperate areas in the Old World are not mere hyperbole.

The influence of the southeasterly wind on the entire Western Cape cannot be overstated. It’s ultimately caused by the confluence of the Agulhas current and Benguela current from Antarctica. The heat gradient between the land and sea and resulting pressure differences in the lower atmosphere produce a moist breeze with a cooling effect of up to 7°C. Its extent diminishes rapidly as you move further inland.

Hemel-en-Aarde: still a benchmark region for pinot and chardonnay

Hamilton Russell Vineyards one of Africa’s most southerly wine estates, situated close to the ocean in the appellation of Hemel-en-Aarde. Photo credits: Hamilton Russell Vineyards.

One of the most exposed areas to this phenomenon is Hemel-en-Aarde. Thanks to the pioneering efforts of Hamilton Russell Vineyards, the region — formerly part of the larger Overberg district but now a ward of Walker Bay — has been famous for some time now. The valley opens up just 1.5km from the ocean, and its narrow sides help to channel the maritime airflow.

Hamilton Russell’s pinots and chardonnays, crafted in a fine, savory style that wouldn’t go amiss in the Cote de Nuits, are still a highlight of our annual South African tasting. On a par with them is Bouchard Finlayson, which produces fine, Burgundy-inspired bottlings, as well as the sensational pinot noir/sangiovese blend Hannibal. Newton Johnson is another producer to watch and catching up quickly with their pinot noir and a very succulent GSM blend.

Why Elgin’s flinty, zesty chardonnays are worth buying

Neighboring Elgin, up to the ‘80s solely a focus for fruit farmers, is predominantly planted to sauvignon blanc. However, we were particularly impressed by the chardonnays. The high-altitude yet coastal district is completely enclosed by the Hottentots Holland Mountains, and the average summer temperature reaches a mere 20°C. The likes of Richard Kershaw Wines, Lothian Vineyards and Paserene — the latter is a project of Martin Smith who previously worked at Vilafonte — are all making edgy chardonnays with a characteristic stony undertone. They are worth seeking out.

Traditional areas such as Constantia are also making excellent cool-climate wines

Meanwhile, Constantia remains proof that not all of South Africa’s cool-climate regions are part of a new wave of wine production. Salty gusts have battered the vines here on the Cape Peninsula for over three centuries.

“You’ve got to be very attentive working with these maritime conditions in Constantia,” affirms Du Toit Hoffman of Eagles’ Nest winery. “The winds can be so strong that the vines might even get knocked over, and then there’s the risk of disease from the dampness.” Cape vintners will tell you that, if anything, achieving ripeness can be more of a problem than overripeness in more marginal areas.

A fourth-generation family wine estate, Kanonkop is located on the lower slopes of the Simonsberg Mountain in the Stellenbosch region of the Cape. Photo credits: Kanonkop Estate.

While the ancient sweet wine recipes of Klein and Groot Constantia are longtime winners (95 points and 93 points respectively this year), we found some of the dry whites a little herbaceous and tart. With that said, we are very enthusiastic about the Bordeaux blends and syrahs being made here — especially on the less shady and warmer sites where the Constantia mountain turns towards Table Mountain.

Stellenbosch’s top subregions of Helderberg and Simonsberg impress

Of course, more traditional areas such as Stellenbosch do get very hot in the summer months. Even so, South Africa’s wine epicenter doesn’t tend to suffer the same heat spikes that say Napa Valley does, let alone Tuscany. Topography, distance from the coastline and site exposure play a huge role in the region as south-facing vineyards capture much more of the sea breeze.

The warmer, inland Simonsberg-Stellenbosch mountain ward produced our best pinotage this year from Kanonkop (95 points) and excellent riper chenin blends, including Laurens Campher from Muratie (93 points). For cooler top regions, Helderberg continues to differentiate itself, particularly with syrah blends such as Post House and Anwilka.

The Swartland is making some of the most exciting wines in South Africa with fresh, terroir-driven syrah and chenin blanc

On the subject of syrah — a variety that we overall believe to be South Africa’s most exciting one — no article on Cape wine would be complete without catching up on the developments in Swartland.

Mullineux’s primary focus is on bottling syrah and chenin according to soil type, maintaining it has the greatest influence on terroir in the Swartland.

The situation is anything but cool-climate. The rolling hills of wheat, occasionally punctuated by small, mountainous outcrops that nest oases viable for viticulture, are torrid and unforgiving. Average summer temperatures top 25°C. Yet, the best wines here always show quite unexpected vibrancy and purity.

Unlike elsewhere, the ocean offers little respite to the hot, continental landscape. Instead, it all comes down to the skill of some of the country’s most talented winemakers, who are now refining their skills with syrah and chenin after the so-called “Swartland Revolution.”

“For sun protection, the bush-vines act as umbrellas, protecting the grapes from most angles,” says Andrea Mullineux, who with her husband Chris made some of the highest-scoring wines in our report this year. “With the trellised vineyards, we keep more leaves around the fruiting zone to prevent sunburn. We also don’t work the vineyards in the heat of midday, unless it is for weed removal.”

The paradox is that though water is scant and the soil delicate and poor, it’s the most decrepit, dry-farmed bush vines that bear the best fruit here. Their low-yielding, gnarled trunks cling to some of the most timeworn rock formations in the world.

“Old vines are the survivors. If a vineyard can live for 50 to 80 or more years without irrigation in our weather conditions, you know it is happy, healthy and balanced… Planting on the contours [i.e. laterally rather than down a slope] will slow water runoff allowing it to saturate the ground in the winter months. This also conserves the topsoil as the Swartland (and South Africa) has some of the oldest viticultural soils in the world, so they are very fragile.”

Watch out Australia, South Africa is catching up!

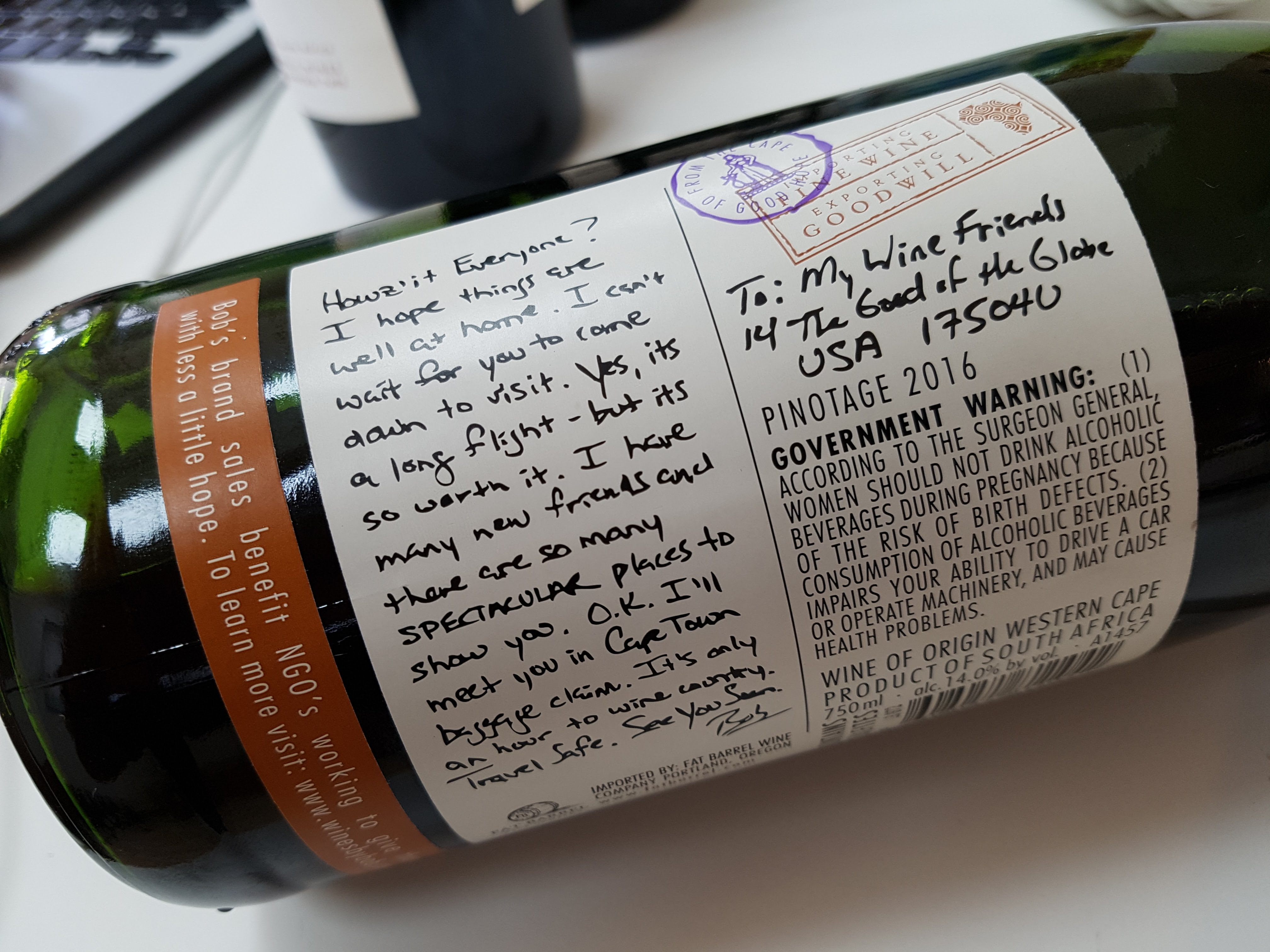

A special handwritten note on the bottle of Bob’s Pinotage Western Cape 2016 that we tasted. We hope to see you soon, Bob!

No doubt a fine-tuning of viticulture and experimentation is afoot across the Cape. While the whites are starting to show real consistency, the quality of the reds seems to be slightly more uneven — but more spectacular when producers get it right.

South Africa might lag behind its natural competitors such as Australia and South America for now, but it’s important to remember how young the modern wine industry really is.

The once all-powerful KWV cooperative only ended its quota system in 1992, which heavily restricted varieties and their planting areas. Only at the turn of the century was the leafroll virus, which hampers quality before ultimately killing a vine, brought under control. And of course, then there was the demise of the apartheid regime in 1994.

“The best sites for vineyards are the ones being planted now,” contends Anton du Toit. “So, imagine what will happen years from now when those vines reach full maturity.”

Jason Snell of The Drift agrees: “South Africa has to be more regional. We should be known for Stellenbosch, or we should be known for Elgin or we should be known for the Swartland. The hottest vintage ever in Stellenbosch was the coolest vintage ever in Elgin even though it’s just on the other side of the mountain. We have to find the variety that suits each individual place. I think our grandchildren will know our lands best.” — Contributing Editor Jack Suckling