It’s hard to define really what a new frontier is when it comes to wine, but, as they say, “I know it when I see it.” Today, there are new frontiers appearing all over the place, from the Yantai region in China to Mexico’s Guadalupe Valley, to the U.S. mid-Atlantic, to South Africa’s Klein Karoo.

How about Sweden, anyone? Last June, on a warm, sunny night, at about 10:30 PM on a terrace in Stockholm, I couldn’t help thinking about this. A diplomat friend had assembled a group of Swedish wines to taste. “You’re trying things most Swedes have never even seen,” he said.

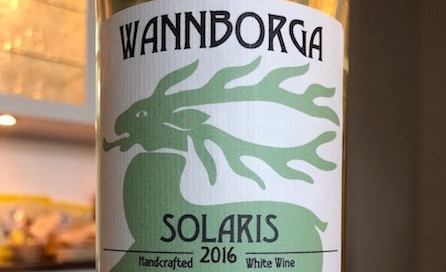

Solaris is a crossing bred in 1975 by Norbert Becker in Freiburg, Germany. The resistant grape is commonly used in harsher, marginal climates for wine production such as in Sweden.

The wines were from different regions in Sweden, including Oresund and the Islands of Gotland and Oland. Most were made from vinifera varieties such as solaris, a grape developed in European research institutes over the last 70 years that generally produces balanced table wines. The most seductive was a bright golden solaris with a reindeer on the label, which reminded me of a good Jurancon sec. It was perhaps even more reminiscent of Virginia’s notable, bone-dry petit mansengs. The tasting notes on some of the bottles got me into the spirit of things, referencing arctic fruit such as lingonberries and cloudberries and sending me scrambling to the market the next day.

It was exciting stuff — sort of a surreal moment that begged the question of how even to think about new frontiers in wine.

They are obviously partly geographic, but that’s not even half the story. They are inextricably tied to human creativity and passion, qualities that drive and dare to test limits that seem to be part of the DNA of the best winemakers in the world, many of whom will be at our Great Wines of the World event next month in Hong Kong. Science, including unprecedented mastery of plant genetics, is a key element, too. Add a burgeoning global middle class, better wine-educated consumers than ever, and the intense wine interest of millennials worldwide, and you get a feel for the remarkable and truly diverse time the wine-loving world is experiencing.

JamesSuckling.com is on the cusp of this story. It’s woven into our coverage of the nearly 22,000 wines we will have tasted by the end of this year. However, the story isn’t only about extreme geography, although that is fun. New frontiers also include regions with ancient roots. How else to think about the transformation of winemaking in Spain or Southern Italy in the last few decades, with the surging quality and elegance of wines from local and international varieties alike? Or the Rhine renaissance, or Bordeaux’s particularly quality-driven step into the 21st century to make less overextracted and high-octane wines? Astoundingly good Slovenian pinot noir and sauvignon blanc?

I thought a lot about new frontiers when I was in Margaret River, south of Perth, last year. So many of the Bordeaux-variety wines there, in the most maritime-influenced wine-producing region in Australia, are stunning in their elegance and class. As a region, it’s a relative newcomer to the scene. China, of course, is a big part of the new frontiers story, both from production and consumption points of view.

The vineyards of Monsoon Valley near Hua Hin, a coastal resort town on the Gulf of Thailand. Known more for its popular beaches and spicy food, Thailand has garnered a number of high scores recently from JamesSuckling.com despite an exorbitant tax regime and a harsh tropical climate.

The most far-flung new frontiers of all though have to be those literally outside the boundaries of conventional wine production — usually considered between 30 and 50 degrees latitude. Winemaking at the tropics is not without immense challenges. Yet countries such as Thailand have proven (check out the surprising results of our latest rosé competition in the Kingdom, for instance) that great winemaking knows no geographic limits. Or consider India’s Nashik, north of Mumbai in Maharashtra state. It’s another outlandish wine region, the grapes being grown at an elevation of 2,000 feet by hundreds of small farmers that serve a growing domestic and export market.

One of the most compelling and exciting “new frontiers” wine stories in the world will be closer to home for many readers. It’s the revolution in quality of regional United States wine.

Napa and other leading West-Coast appellations understandably drive the narrative of American wines.

However, keep your eyes on the rest of the country, too. Amazing, world-class wines are emerging from a multitude of American Viticultural Regions (AVAs) ranging from Snake River Valley in Idaho, to Grand Valley in Colorado, to Texas High Plains, to Yadkin Valley in North Carolina, to Shenandoah Valley in Virginia, to Outer Coastal Plain in New Jersey.

We have already reported quite recently on many of the top wines of Virginia, Finger Lakes, Pennsylvania, Arizona and Michigan.

America has a staggeringly rich and diverse wine heritage, dating from the late 16th century, although much of the early viticultural history is still subject to contention. Many states, including New Mexico, Ohio, Missouri, New York and Virginia had huge and successful wine industries by the late 19th century. They were all crushed by Prohibition (1920-33) and only now are production levels in some states even getting close to what they were 120 years ago.

Virginia’s historic Barboursville Winery in Barboursville, Virginia, will be the main site of JamesSuckling.com’s “The Great American Tasting.” James Suckling, Nick Stock and Stuart Pigott will taste around 1,000 wines from lesser-known regions across the United States.

I believe the quality is standout. Today’s best producers know their terroirs and clones and have an artfulness and drive that links them to their best peers the world over. They are making fine wines, at reasonable prices, that will simply blow your mind.

We want you to know more about this big and underreported story from the American heartland.

That’s why you need to stay tuned for our major upcoming report “The Great American Tasting.” James and his senior tasting team will gather October 7-12 at Virginia’s historic Barboursville Vineyards to blind taste and review up to a thousand of the best regional American wines, from producers throughout the country. It’s integral to our approach to consumers, producers and the trade — telling the story of the world’s great wines.

We’ll be able to say a lot more then, and we hope you’ll join us on our journey in this exciting new frontier! — William McIlhenny, Strategy