Is the future for Alsace red or white?

The lanky, usually imposing figure of Maurice Barthelmé, co-owner of Domaine Albert Mann, is crouched down at full stretch, tenderly inspecting his nascent pinot noir vines with his gnarled hands. Yet the tenuous, pale-green shoots protruding from his Pfersigberg vineyard in southern Alsace belie the stout, aged rootstock below.

“If I had pulled out these pinot gris vines, I would have had to wait decades now to get excellent quality pinot noir,” he explains. “By keeping them but grafting over pinot noir, I end up with the equivalent of old vines within a couple of years. They have the same genetic material after all. Besides, it was getting too hot here for pinot gris.”

Rising global temperatures have been a boon to red wine from Alsace. It was not so long ago that Alsatian pinot noir was thin, acidic and often made in a rosé style. If any wines from the ‘90s, when the variety began turning a corner, had the necessary body, they tended to be at the very least slightly overripe, suggesting protracted hang times were necessary. But pinot noir acreage has doubled in the last 30 years to account for over 10 percent of plantings, and after our week-long tasting of over 500 wines in the region, we can safely say it is now one of the most exciting categories in Alsace.

Alsace pinot noir excitement

Today’s pinot noirs from the likes of Domaine Albert Mann, Muré, Domaine Kirrenbourg and Domaine Valentin Zusslin are ripe and structured yet balanced and taut, establishing a style somewhere between Burgundy and Oregon that’s unique in its own right. Many have a pretty whole-berry lift to them with a subtly played but rarely overdone hint of oak. The top sites tend to be south-facing with limestone soils and can truly compete with the best in the world.

Of course, Alsace remains predominantly white wine country, and this played out in our annual review: eight of the top 10 positions were taken by riesling, gewurztraminer or pinot gris. Riesling remains king and gewurztraminer, especially examples from the 2017 vintage, can be stunning; pinot gris is delicious in the right hands. Nevertheless, whereas global warming must surely be seen as beneficial for red wine production, we were slightly dismayed that this has pushed some producers further off course in the dry/sweet continuum for whites.

Jack with a 2012 riesling from the fabled Clos Ste. Hune.

“Some people need an electroshock around here! Apart from late-harvest styles, Alsatian wines are supposed to be dry,” admonished the head of the celebrated family dynasty of Hugel & Fils, Marc Hugel, as we chatted over dinner on the last night of our trip. His honest words, not to mention his steely whites, seemed to cut right through the haze of rich, unctuous French food and garish and rustic surroundings in one of the local medieval villages. Alsace does have a real problem in that it is now very difficult to find dry or perceptibly dry whites at all.

“Consider that 30 years ago 99 percent of whites in Alsace had 2g/l of sugar or less. Now you are hard-pushed to find anything under 5g/l,” continues Hugel. “Yes, it’s hotter now than it was when I was a child, maybe a few degrees warmer, but do you see Montrachet or Haut-Brion Blanc becoming sweet? That’s a false answer to a wider problem!”

Dry white wine from Alsace now rare

So, what is the answer to this conundrum? It was the number one question on our minds as Contributing Editor Nick Stock, James and I tackled each successive flight. Bone-dry wines were certainly a minority, and a number were weighed down by too much sweetness.

Although we tend to prefer drier styles, a touch of sugar can work if in balance with the fruit, acidity and alcohol. Even so, it remains somewhat daunting veering from extreme sweetness on one end to apparent dryness on the other — all within the same category. And it does little for Alsace’s identity and export sales.

Speaking with producers you hear many explanations — some more outlandish than the next. The high acidities of Alsace require a degree of sweetness for balance, say some. One vigneron even claimed that since there is now so much organic and biodynamic viticulture, it’s no longer possible to ferment 100 percent dry due to the low alcohol tolerance of native yeasts.

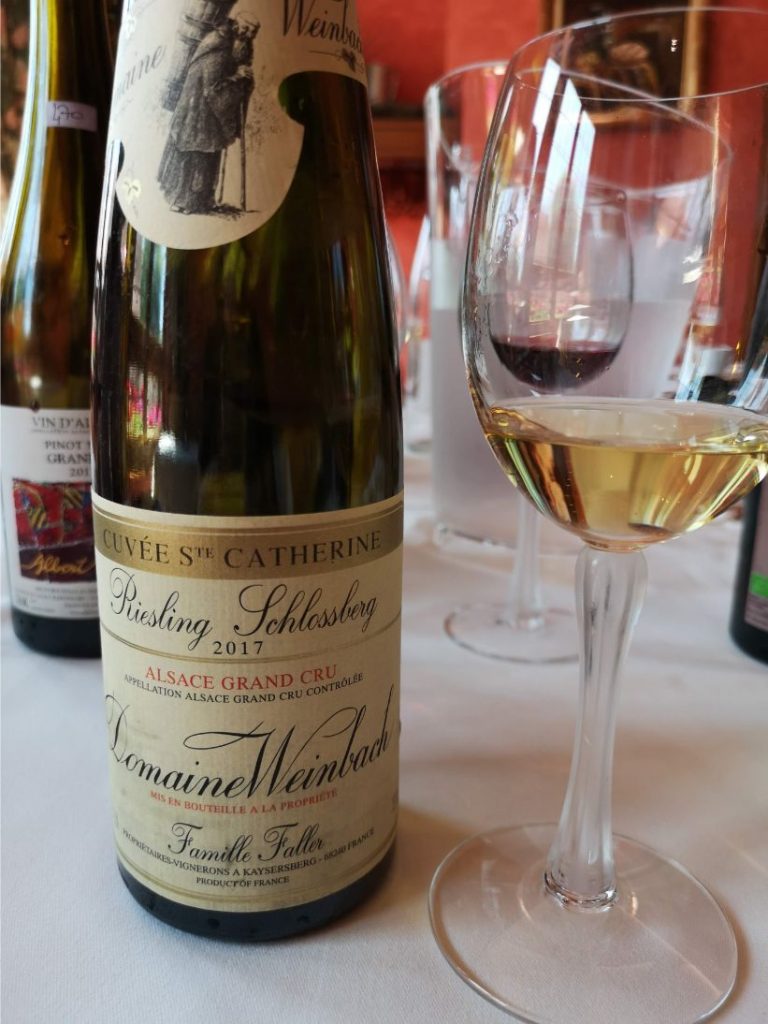

The purity of fruit in this 2017 Cuvée Ste. Catherine from Domaine Weinbach is really something: sliced apples, peaches, lemons and hot stones.

Too hot to make dry whites?

I cannot agree that it is simply too hot now in Alsace to make dry whites. This argument claims that given the resulting high brix levels, winemakers have no choice but to leave some sweetness to avoid getting a flabby, alcoholic wine. This just about holds water for gewurztraminer where to get the required phenolic ripeness you need to pick at 15 or 16 percent potential alcohol. But for the other varieties, the fact is that there are numerous areas in the world making successful wines with zero perceptible sweetness, from the same grape varieties, in hotter climates. You only need to look at Alto Adige or the Barossa, which have higher growing degree day readings and heat extremes. Perhaps excessively low yields and late harvest periods are the main concerns?

“Alsace is really difficult to understand sometimes,” conceded Julien Trimbach of the namesake wine-producing estate, as we ascended — or more accurately ambled, for the vineyard is surprisingly flat — through the fabled Clos Ste. Hune. Even at ground level, between the two outlying trellis posts, you can easily see the entire lay of this 1.6ha micro-parcel: free-ranging clumps of grass divide up immaculately trimmed rows of low-yielding vines, with calcareous, fossilized stones — what the locals call Muschelkalk — poking out in barer patches; the 15th century fortified church of Hunawihr, rising in the background on a hill above the hamlet consecrated to St. Hune, completes the bucolic scene.

Trimbach is convinced that it’s man rather than these natural surroundings that makes sweet, heavy wines that should really be dry. “This is something that you choose. You pick late and you don’t ferment dry,” he insists. “We usually have little more than 4g/l of residual sugar in our wines. Those who make only sweet wines are making market-driven wines. They think that tourists and the domestic market appreciate that style, but I think they’re making a big mistake.”

He is certainly on to something — his Trimbach Riesling Alsace Clos Ste. Hune 2016 earned 98 points.

Regardless of the reasons, like it or not Alsatian wines are now, for the most part, sweet. We can only recommend, if you are not a fan of the more cumbersome interpretations, to opt for producers committed to making largely dry wines. Among them, look out for Domaine Weinbach, Hugel, Josmeyer, Muré and Trimbach.

This J. Becker pinot noir showed ripe strawberry and plum aromas and flavors.

Alsace vintage rundown

On the subject of vintages, generally speaking these can be split into the colder, more “classic” and hotter, more “modern”. The latter include 2018, 2017 and 2015, whereas 2016, 2014 and 2013 fit more of the traditional mould.

That said, unlike elsewhere in Europe, 2017 was something of a goldilocks harvest in Alsace where the summer was hot and dry but not extreme, and the spring brought the necessary rains. Conversely, yields were down due to an unforgiving bout of frost, which decimated some 4,500 hectares; many lost as much as 100 percent of their crop in some areas. As previously mentioned, gewurztraminer did especially well, but there are many fantastic rieslings and pinot gris, too. Most wines had the necessary concentration but the creme de la creme also achieved balance and finesse. Buy at will.

2018 was quite a bit hotter — even earlier than in 2017, at the end of August, and the wines are more open and overt. We look forward to tasting more wines from this vintage next year as they begin coming out on the market.

By contrast, 2016 was a very cool year with most picking occurring during October. Yields tended to be higher, but some crop was lost to humid conditions and mildew towards the beginning of the year. The wines are quite tight and edgy with pronounced acidity.

In 2015, a humid winter was followed by a searing, dry summer; Maurice Barthelmé of Domaine Albert Mann says that sugar levels increased by two and a half degrees every day over a 10-day period, instead of the usual one degree. The wines are juicy and flamboyant with the best also possessing balance. Occasionally, some of the sweeter styles can be a little overblown.

Alsace’s sweet wine excellence

Of course, there is nothing wrong with Vendanges Tardives or Selections de Grains Nobles (SGN). On the contrary, these are some of the highest-scoring wines listed below and amazingly they often taste less sweet than wines you might expect to taste dry. If Hugel’s two “S” SGNs, one a 2015 riesling and the other a 2008 gewurtz, don’t take your breath away, then nothing will. The wines are wondrously dense yet agile with an almighty intensity and complexity of flavor and nuance. Botrytis-influenced grapes still have an awe-inspiring capacity to make wines that beggar belief in these parts.

An earthy, historic bottle of Hugel’s Jubilee pinot noir.

The only problem is that these kinds of rarities are in miniscule supply, and not just because the market doesn’t have an appetite for them. “What botrytis? I don’t know what has happened to botrytis!” quips Hugel. “The last crop with a significant proportion of botrytis was in 1995. Maybe it’s just drier now. But I think it’s also because we stopped using nitrogen in the vineyard and dropped down the vigor.”

As the climate changes and producers figure out exactly what path they want to take, another topic in flux is that of the appellation system. Grand Crus in Alsace have been problematic ever since the first one, Schlossberg, was established in 1975. That’s exactly where I found myself on a sultry but breezy Friday morning in July with Eddie Faller, the newest generation of the family that owns Domaine Weinbach. There was a real sense of excitement, not just because the Fallers are some of the most precise winemakers out there but because their Schlossberg bottlings, especially the Cuvée Ste. Catherine, are so keenly transparent and subtly powerful. We gave the Cuvée Ste. Catherine 98 points.

After gambolling along up treacherous cliffs in four-wheel-drive, we come to a wide vantage point next to a ruined castle; the village of Kaysersberg glistens below against the lusciously viridescent backdrop of the Vosges Mountains. Despite the spectacular panorama, the reasons for controversy become immediately apparent. While the extreme, sheer rock face of the Schlossberg vineyard with its compacted granite strata and wafer-thin topsoils account for the racy yet potent expressions this site can produce, as it disappears out of view the land becomes heavier and the exposition changes from south to east. Disappointingly, this is not a unified terroir in any sense — in fact, a group of trees definitively splits this coveted piece of land in two.

Alsace wines lack consistency

Examples such as these are common in Alsace. Grand Crus still tend to be far too large and heterogenous, to the extent that they often lose their significance altogether. Recent initiatives to bring in Premier Crus and allow pinot noir to feature on Grand Cru labels should be welcomed, but will amount to little if the authorities can’t sort out the underlying problems. We remarked while tasting that Alsace has the largest variance in quality between Grand Crus. The fact that brands are more of an indication of quality than vineyard sites should be a useful guidance point for the reader but not a happy state of affairs.

“There’s a distinct lack of visibility for certain Grand Crus,” agrees Faller. “Many sites are owned by co-operatives who are declassifying crop or even labelling Grand Cru at cheap prices.”

Consider that in Schlossberg the yields are as low as 18hl/ha. The legal limit is 80l/ha!

Alsace remains an underrated and underexplored wine-growing region internationally, especially in the United States and Asia where sales have floundered. This is a great shame as the area can claim some of the most geologically diverse soils and unique microclimates on earth. Moreover, the large proportions of organic and biodynamic agriculture and expert, non-intervention winemaking with minimal oak and little malolactic (usually none of the above) set a responsible example for the rest of the wine industry.

White wines from the region are at a crossroads, but the case for great pinot noir has never been stronger. “To be a top producer in Alsace today, you need to make a top red,” explains Samuel Tottoli of Kirrenbourg and Armand Hurst. “That’s a big change. This is especially true for the export market. We are replacing red Burgundy in some markets.”

This should be music to wine lovers’ ears, not least because prices in Alsace are so reasonable. Equipped with its burgeoning red wine scene, nobody can now doubt that this quirky, French, Germanic, Catholic and Protestant melting pot of influences has all the makings of a viticultural nirvana. – Jack Suckling, contributing editor

This report was created in partnership with Lalique, creators of the Lalique James Suckling 100 Points Glass line.