Despite the continued debate in Champagne over whether small growers or top houses make the best wines, many leading winemakers in the region believe that both types of wines are a plus to the region – and James Suckling and my recent tastings in Champagne of almost 400 wines more than support this view.

“People want to contrast growers and big houses, saying that growers represent terroir. But if 100 percent of the land belonged to me, the decisions would be the same, and we are lucky to have diversity of terroirs and of vine growers,” said Julie Cavil, the cellar master of prestigious Champagne house Krug, adding that quality-focused houses like Krug aim to translate and express terroir, despite not owning most of its vineyards.

Added Lucie Pereyre de Nonancourt, whose family own the Champagne house Laurent-Perrier: “The houses have done work on parcels, but it gets lost in communication. I think growers are a good alternative to big houses because they communicate it to the consumers. They do not have as much reserve wine or capacity so they have to adapt, but that’s nice because it’s an alternative.”

Take Dom Perignon in contrast – a success story of branding and of great wine, considering its large production. The house works with around 1,000 hectares and is at liberty to select around 50 percent of the fruit to find the very best grapes each year. Four of the wines in our top 20 from our tastings this summer were from Dom Perignon: their 2008, 2010 and 2013 vintages, alongside Dom Pérignon Champagne P2 2002.

“Our idea is to find the best grapes every year,” said cellar master Vincent Chaperon. “All Dom Perignon is constructed from polarizations and parcels with different characteristics. This is our philosophic principle.”

Grower-vigneron Pascal Agrapart, of Champagne Agrapart et Fils, pointed out that less resourceful growers are not tied to house styles and are free to make decisions at every level. And now, what was once considered the signature of growers – single-parcel Champagnes – is prized by many large Champagne houses, too.

“I like to make wines that I really like to drink. That’s not to say that I don’t like others, but it’s my signature [to] let the terroir speak,” Agrapart said.

“When I started, they told me I was crazy to focus on parcels, but now also the big houses do that, like the clos of Mesnil and Ambonnay,” he pointed out, referring to the walled 1.84- and 0.68-hectare plots of Clos du Mesnil and Clos d’Ambonnay owned by Krug.

TERROIR ON A PLATE

What stood out in our tastings was the diversity of wine styles and winemaking philosophies, rather than a question of quality or the transparency of terroir. In fact, we found perfect wines on both sides. Within the first 24 hours of our trip in June, we were rendered almost speechless by a wine that has reached almost cult status. At only 800 bottles of production, the Henri Giraud Champagne Argonne Brut Rosé 2012 is in a category of its own, incomparable to any of the other rosés we tasted, with undeniable power and intellectual energy, yet soft and refined at the same time.

When we pointed out the distinctive rusty minerality in the wine, alongside citrus, stone fruit and spice, Henri Giraud cellar master Sebastien Le Golvet left the room and returned with two piles of crumbled rock: one white clay and the other red, iron oxide-rich soil. Terroir on a plate.

Le Golvet explained that the soils around Ay, the commune where Henri Giraud is based, has lots of iron oxide. “This gives tension to the wine and very sharp acidity, and also shows the fruit of pinot noir; clay gives openness,” he said.

Le Golvet is obsessed with terroir. Champagne Henri Giraud is unique in fixating not only on the parcel-specific provenance of their grapes, but also on the wood they use to make their barrels, down to the exact geolocation of oak trees. As far as we know, they are the only producer with direct traceability of the wines to the origin of the oak barrels. He says he is totally organic in his vineyards in order to maintain the purity of the fruit.

“We only work with small barrels using oak from the Argonne Forest,” he said. “The wood we use is 200 to 300 years old, and we age the oak for three to five years [before making the barrels]. I don’t want to “boiser” [give woody elements to] the wines; I just want to let the terroir of Ay express itself through the wood of Argonne.”

Another perfect wine that we tasted was from a longstanding Champagne house, and a very different one in terms of winemaking. The Laurent-Perrier Champagne Grand Siècle Les Réserves N.20 NV is a limited-edition Champagne that will be released only in magnum in September. Like all their Grand Siecles, it is a blend of three vintages, in this case 1999, 1997 and 1996, to “re-create a perfect year.” It spent 21 years on the lees before disgorgement, resulting in a complex, layered and intense wine, with a round, oily texture, and fantastic umami notes of preserved lemon, quince, sea urchin, mushroom and salted caramel. It a blend of 54 percent chardonnay and 46 percent pinot noir.

“Grand Siecle was the first of its concept,” said Edouard Cossy, Laurent-Perrier’s global director. They only declare vintages when they are deemed high enough in quality, drawing a contrast to many houses’ vintage prestige cuvees. And we again launched into the discussion of growers versus houses.

“If you look at winegrower perspective, they go for small parcel to show terroir,” Cossy said. “If you look at houses, they used to do mostly vintages, but they are more often doing blends now and declaring exactly what is in the blend.”

Laurent-Perrier was innovative in being among the first to use stainless steel in Champagne in the 1970s, and today exclusively vinify and store their wines in steel. “Every step is made to avoid oxygen and to maintain the purity, the freshness, the aromatics of the wine,” said Pereyre de Nonancourt. “That’s why the wine has a long life in front of it.”

With such contrasts in styles and character, the future of Champagne now lies in distinguishing between specific parcels and vineyard sites – in particular the soil diversity within specific villages. Both growers and houses are recognising that this is a point of differentiation and will be talking more about it. Champagne lovers already know that some of the most expensive bottles are single-vineyard wines, and more and more are coming in the future.

In our top 10 wines, two were from single walled vineyards (clos): Billecart-Salmon Champagne Le Clos St.-Hilaire Brut 2006 and Krug Champagne Clos du Mesnil Blanc de Blancs Brut 2008. It’s obvious to talk about terroir here – Le Clos St.-Hilaire has amazing precision, made from a single-parcel pinot noir, with fascinating spicy clove and white pepper notes to the red and yellow fruit. Clos du Mesnil, in contrast, is 100 percent chardonnay: tight, powerful and structured with a sharp backbone of acidity.

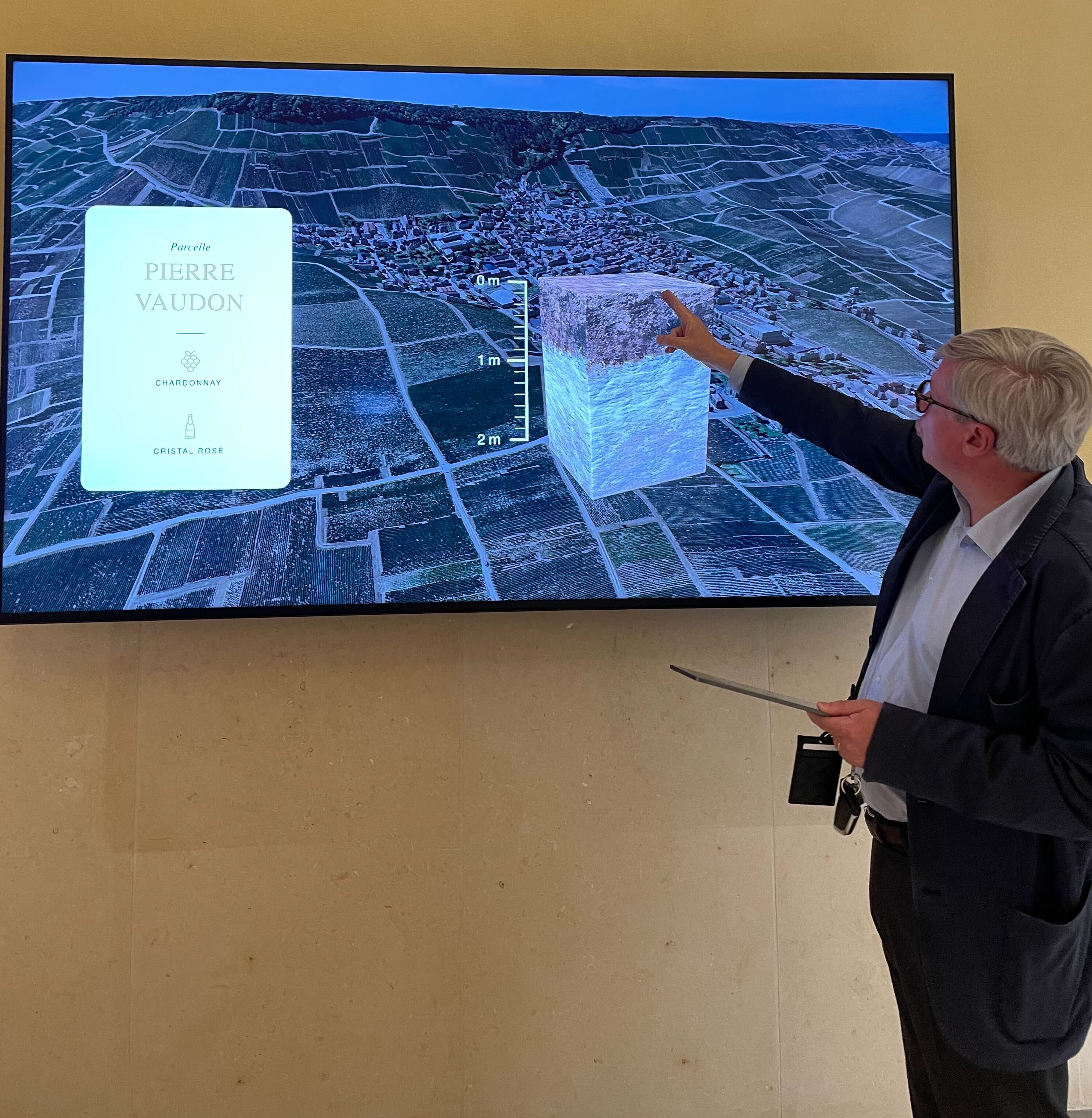

But even wines that are made from blends of grapes grown across Champagne are presenting an identity built from the characteristics of their specific parcels and their soils. Louis Roederer Cristal is an example of this – a blend of the house’s own Grand Crus parcels in the Montagne de Reims, the Marne Valley and the Cote des Blancs. Even their regular non-vintage cuvees have a precise plot-by-plot approach, clearly communicated on an interactive map at the house in Reims, indicating location, altitude, aspect, soil composition and depth, and more.

“What we try to make at Louis Roederer are wines that reflect the soil,” said cellar master Jean-Baptiste Lecaillon. To illustrate his point, he showed us several specific plots on a 3D video map, such as the biodynamically farmed parcel Villers, located in Ay, which is a component of Cristal Rosé. These vineyards are just above the vineyards used for Dom Perignon’s rosé, and has the same chalky soils, resulting in perfumed, elegant pinot noir.

“I call it the Musigny,” said Lecaillon, because Cristal and Dom Perignon make some of their best rosé Champagnes from the same area in Ay. At the end of the day, he said, “it’s the soils that make the taste of Champagne.”

Lecaillon also made one of the five 100-point wines from our tastings – the recently released Louis Roederer Champagne Cristal 2008 in magnum. It’s released later than the normal bottles of Cristal, which we gave 100 points to last year. This is an incredibly structured and precise Champagne, a benchmark blend of 60 percent pinot noir and 40 percent chardonnay. With an extra couple of years on the lees, this special release is one for the cellar.

READ MORE: TOP 100 WINES OF FRANCE 2021

But it wasn’t all bubbles at Louis Roederer. We tasted the newest (and only second) vintage of their chardonnay, the Louis Roederer Coteaux Champenois Camille Hommage Blanc 2019, and pinot noir, Louis Roederer Coteaux Champenois Camille Hommage 2019. These are still wines made from single plots in Le Mesnil-sur-Oger and Mareuil-sur-Ay, respectively. We were particularly impressed by Camille Hommage Blanc: intense, beautifully compact yet elegant, with sharp acidity but a creamy and refined texture. Three quarters of the chardonnay was matured in clayvers made of sandstone (less porous compared with terracotta; also used at Henri Giraud and other wineries), with the rest in new barrels. We only wish they made more than just over 1,600 bottles, each individually numbered.

With climate change, Coteaux Champenois seems to be a growing category for some Champagne producers. Both Lecaillon at Louis Roederer and Le Golvet at Henri Giraud said that demand is overwhelming for their limited production; others confessed that it was difficult to sell. We only tasted 10 Coteaux Champenois and one Rosé des Riceys (which was more like a Burgundian pinot), but these already seem to show excellent potential.

“There is extraordinary potential for Coteaux Champenois, for pinot noir,” said Le Golvet. We were certainly impressed by both the Henri Giraud Coteaux Champenois Grand Vin d’Aÿ Rouge Cuvée des Froides Terres 2018, a fragrant and spicy pinot noir made by the “millefeuille” method of sandwiching layers of stems and destemmed whole grapes in fermentation, as well as their chardonnay, the Henri Giraud Coteaux Champenois Aÿ Blanc Grand Cru Cuvée de Croix Courcelles 2019.

ROSÉ REVOLUTION

Some of our highest-scoring wines were rosé Champagnes. The few dozen wine producers and vintages in Champagne that we spoke to said demand seems to be skewed toward prestige rosés rather than across the spectrum.

“Today, the fashion is still Blanc de Blancs while rosé is still comparatively small … but for prestige rosé the market is crazy,” said the president of Champagne De Venoge, Gilles De La Bassetiere. De Venoge Champagne Louis XV Brut Rosé 2012 was the third of our top three rosés, with so much going on in terms of citrus, spice and pastry notes, and with fantastic energy and aging potential.

We found the Blanc de Blancs (17 percent of our tastings) to be of higher quality overall, at an outstanding average score of 93.3 points; followed by rosés (13 percent) at 92.7 points and Blanc de Noirs (6 percent) at 92.2 points. But the wines are consistently high in quality across the board. Of the 446 Champagnes we tasted over the last six months, a mere 5 percent scored under 90 points, while the average score was just under 93 points.

Are these high average scores due to climate change? Several Champagne growers and producers that we spoke to agree that warming temperatures have been favorable for the usually rainy, cool region.

“When I arrived in ‘95, we were harvesting first week of October. Now, it can be end of August. We see the effects of climate change, and in the last 10 years the seasons have been fantastic for Champagne,” said De La Bassetiere.

Some producers voiced concern that some of their vines weren’t getting as much water in their root systems because of compaction of soil. But for vineyards endowed with more water-absorbing chalk content, there is little stress, and indeed the vines thrive and successfully ripen year on year.

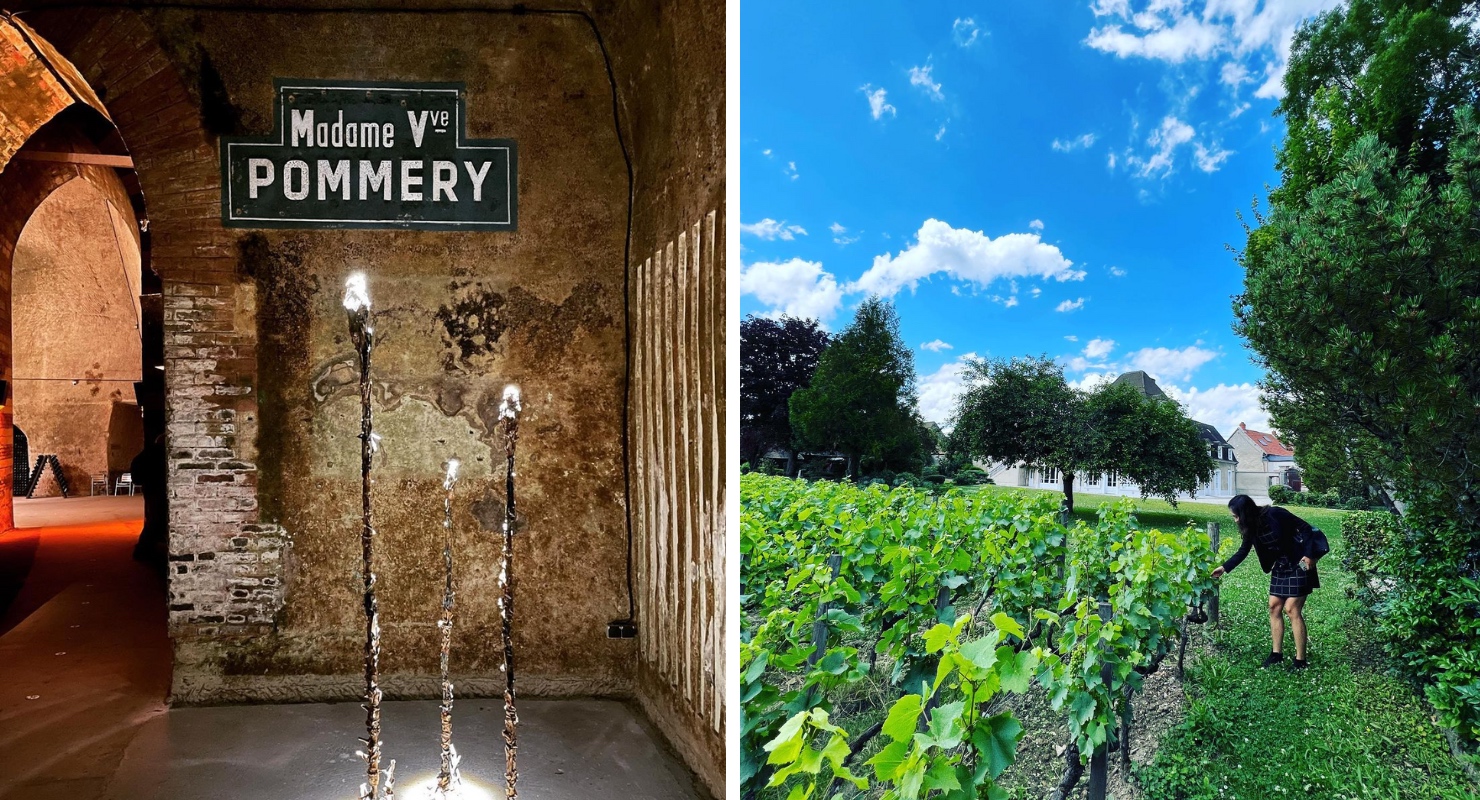

“It has been more an opportunity for the Champagne region in the last 20 years, so I think the overall quality has increased,” said Clement Pierlot, the cellar master at Champagne Pommery. “But we may start to have issues of heat and drought.”

Pierlot also pointed out that Champagne as a brand remains strong. Total production in 2021 increased 32 percent to 322 million bottles over the previous year, with record-breaking exports of 180 million bottles.

He said the pandemic has helped lift at-home consumption of Champagne, with people trying varying brands of bubbly. “It was very important for Champagne,” he said. “It has started a new way of drinking Champagne through the meal at home.”

The increase in Champagne shipments indicates that more people around the world are drinking Champagne, and not just as a festive drink but something that can be enjoyed just about anywhere, including at home, and on any occasion.

Below are our tasting notes from our trip to Champagne last month as well as key wines tasted last year that are still on the market. Here’s to popping open greatness…

– Claire Nesbitt, Associate Editor